Books & Essays

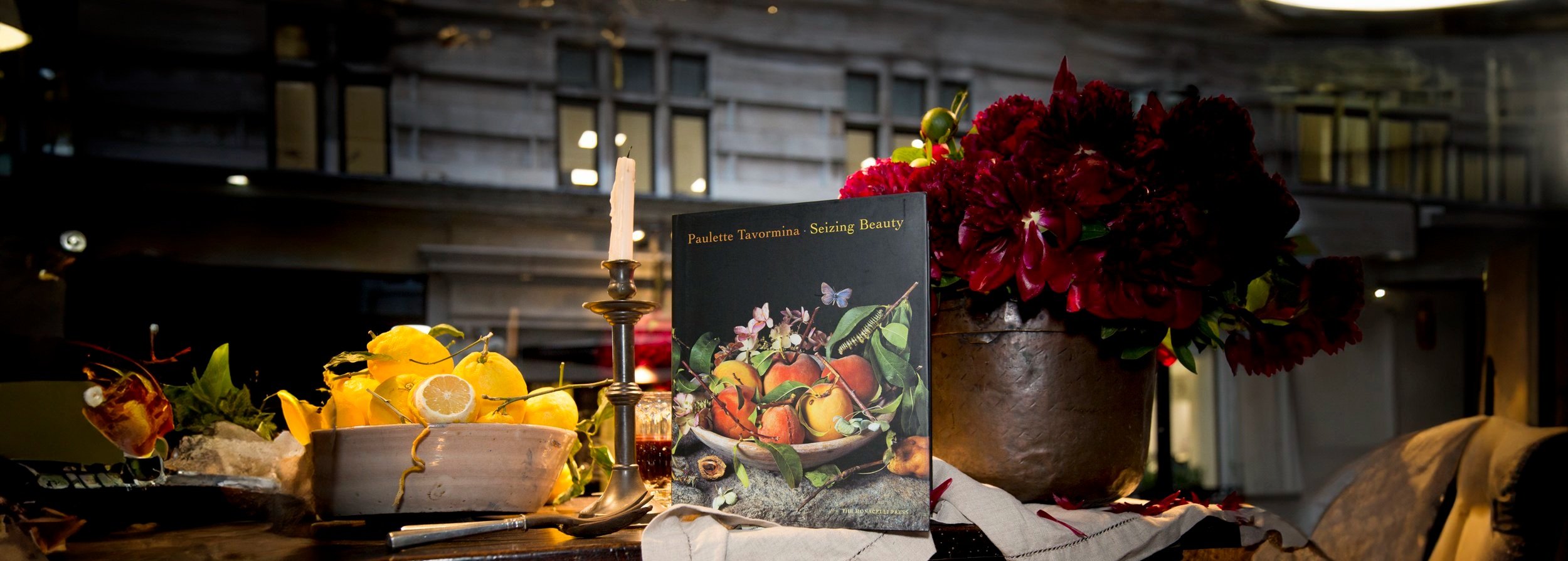

Paulette Tavormina: Seizing Beauty

Photography by Paulette Tavormina

Published by The Monacelli Press | April 2016

Essays by Silvia Malaguzzi, Mark Alice Durant, and Anke Van Wagenberg-Ter Hoeven

Hardcover: 9.25 x 12.25 inches | 23.46 x 31.12 cm | 160 pages | 65 images

ISBN-10 : 1580934560

ISBN-13 : 978-1580934565

PRESS RELEASE

In her sumptuous photographic still lifes replete with flora, food, and artifacts, Paulette Tavormina creates intensely personal interpretations of timeless tableaux. With a painterly perspective reminiscent of Old Masters such as Francisco de Zurbarán, Adriaen Coorte, and Giovanna Garzoni, Tavormina’s meticulously orchestrated and lit photographs are boldly contemporary in their precision.

Paulette Tavormina: Seizing Beauty presents the full array of her seductive and opulent still life series, heirs to the legacy of a cherished art tradition now seen through the lens of photography. Essays by art and photography scholars Silvia Malaguzzi, Mark Alice Durant, and Anke Van Wagenberg-Ter Hoeven delve into the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century sources of Tavormina’s inspiration, her stance in art photography, and how the conventions of yesterday’s painting can transform to make visually stunning photographic art for today. Signed copies can be ordered directly from the artist via email.

BOOK REVIEW: The New York Times

Natura Morta

Sold Out

Photography by Paulette Tavormina

Limited Edition

Essay by Wayne Andersen

Hardcover: 12 x 12 inches | 30.48 x 30.48 cm | 40 pages | 26 images

PRESS RELEASE

Natura Morta, a new photography book by Paulette Tavormina

A new full-color book featuring Tavormina's photography has been published and has an essay "The Many Lives of Paulette Tavormina's Still Lifes" by art historian, Wayne Andersen. The 40-page book measures 12" x 12" and contains 26 of her fine art images.

Essays

Paulette Tavormina ”The Oysters“

Essay by Silvia Malaguzzi, Art Historian And Author, Florence, Italy

Paulette Tavormina’s The Oysters is both seductive and unsettling as it presents in photographic form what anyone with a background in art would instantly recognise as a painting. Tavormina’s camera captures an arrangement of real objects similar to that created by the brushstrokes of Flemish still-life artist Willem Claesz Heda.

Paulette Tavormina Oysters and Lemon, AfterW.C.H., 2008

Still Life by Willem Claesz Heda, circa 1614–1680, El Prado Museum, Madrid

The viewer is misled by the re-creation of a similar setting and the selection of almost identical objects, with only one substantial difference: Claesz Heda achieved a trompe l’oeil effect with pictorial proficiency while in Tavormina’s work it is a natural consequence of photographic technique. Moreover, in transforming a recognizable and datable pictorial subject into photography, the artist turns something intended as an illusion into something real. Tavormina also generates spatial-temporal disorientation by creating a contemporary piece with all the characteristics of the 17th century.

This sophisticated intellectual operation reveals Tavormina’s erudite preferences and makes viewers wonder to what extent Claesz Heda’s cultural climate endures in The Oysters and what belongs to the genuine contemporary sensitivity of the artist-photographer.

A comparison between The Oysters and Claesz Heda’s Still Life located in the El Prado Museum in Madrid is useful. By 1620, Claesz Heda had achieved certain recognition in the Dutch market for 17th century still-life paintings: the elegance and sobriety of his monochromatic ‘Breakfast Pieces’ received the approval of the frugal Calvinist community[1]. The food and vessels he selected reveal many of the refined eating habits and table manners of the wealthy Dutch middle class. Oysters were not merely delicious seafood from the North Sea but symbolised supremacy of the Indian Ocean, recently acquired by the Dutch government for its pearl industry.

Pepper, depicted here in its typical paper cone, was an exotic spice imported from the Far East and therefore rare and expensive and a source of income for traders and the whole country[3]. The Roemer glass was used for tasting fragrant white wine imported from the Rhineland and destined for particular consumers[4].

Every detail contributes to defining the high social status of the clientele of this kind of artwork but a lot more can be deduced by analysing the image in detail. The uneven tablecloth, the partially peeled lemon, the remains on the dishes and the overthrown fruit stand are all traces of human passage. The two glasses evoke a couple drinking together. The firm-based Roemer reflects a man with selective tastes, favouring imported white wine to beer, the national beverage of the Dutch. Meanwhile, the precious façon de Venise goblet refers to the delicate feminine palate. Oysters have been renowned since Roman Antiquity not only as a culinary speciality but also for their aphrodisiac properties and hence allude to the pleasures of both gastronomy and sex[5].

Such details suggest the commissioners were a wealthy couple fond of food and life. Meanwhile the discreet presence of a gold pocket watch reveals the subtle moral intent of the artist.

According to conventions of 17th century Flemish artists, a watch represented a reminder of the passage of time and the transience of worldly possessions and pleasures[6]. Claesz Heda very likely included this time-keeping instrument to warn his commissioners against the risk of expecting the joys of youth to be eternal when in fact time condemns everything and everyone to the same sad end. The watch is absent in Tavormina’s artwork and the melancholy of man’s tragic fate gives way to her joyful celebration of everyday life and its intimate and poetic simplicity.

Oysters reflects a very solitary and private meal, but nonetheless elegant and learned. Alongside the peeled lemon, oysters, a Roemer glass and pepper in a paper cone, the artist intentionally reveals her modernity by introducing a few pink peppercorns, which scientists recently differentiated as an entirely separate genus from black pepper.

Salted capers were little known in Holland in the 17th century and thus reveal the artist’s Sicilian origins. They transpose Oysters from simply an erudite emulation of Claesz Heda’s painting to an independent piece of artwork which is openly and joyfully autobiographic.

http://www.alimentarium.ch/en/home.html

The Exihibition opened at The Alimentarium Museum May 2, 2013 in Vevey, Switzerland

[1] GROOTENBOER Hanneke, The Rhetoric of Perspective, Realism and Illusionism in Seventeenth-century Dutch Still-Life Painting, Chicago and London 2005, p.82.

[2] DE GIROLAMI CHENEY Liana, “The Oyster in dutch genre paintings moral or erotic symbolism”, in Artibus et Historiae (Roma), 8.1987,15, pp. 135-158.

[3] MALAGUZZI Silvia, Il cibo e la Tavola, Milano 2006, pp. 276-277.

[4] JOHNSON Hugh, Il vino: storia tradizione e cultura, Padova 1994, p. 278.

[5] PLATINA Bartolomeo, De honesta voluptate et valetitudine, lib. X, cap. 366.

[6] SULLIVAN Scott A., “A Banquet Piece with Vanitas Implications”, in The Bulletin of Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland), N°61, 1974, p. 281.v

“I will astound

Paris with an apple”

— Paul Cézanne

The Many Lives Of Paulette Tavormina’s Still Lifes

Essay by Wayne V. Andersen, Art Historian

I will astound Paris with an apple

--Paul Cézanne

Still life is a strange and problematic term. Its 17th-Century origin is the Dutch still-leven—the motionless aspect of living nature. A century later in France, where still life painting came late, still-leven became nature morte, dead nature.

In English, a still life is motionless—still, tranquil, static. Stillness can be a condition of the moment or of forever as existing still. A still life doesn’t speak and it can’t listen. It cannot move but it puts the viewer’s eyes in motion. It nourishes inquisitive eyes and assures an abundance of visual life. Eyes are always in motion. In death, eyes are the first to become still—still-leven, then nature morte.

My photographs tell stories. The “Figs” express the Sicilian family history. I can imagine they are from my brother’s tree that was a graft from my father’s tree and in turn a graft of my grandfather’s tree. Snails on the branches are from my cousin’s villa in Palermo, next to the abandoned Giuseppe Lampedusa’s villa (author of Il Gattopardo, The Leopard). Lampedusa died in 1957. Snails at his villa look the same as snails at my cousin’s villa.

Tavormina’s still lifes are inspired by the Dutch, Spanish, and Italian still lifes of the Golden Age. But what the prototypes meant in the past remains in the past. We see the past only with eyes in the present. As T.S. Eliot said, “The past should be altered by the present as much as the present is directed by the past.” The past cannot be relived but can be converted into meaning for the present. The human condition is incessantly evolving, trapped in the gravitation pull of the future. Tavormina’s still lifes are her poetic way of expressing respect for the human condition.

The Crabs are playful — back to back. It took an entire week to shoot this picture, arranging the crabs, adjusting the lighting, putting the crabs back in the refrigerator every night, taking them out in the morning and starting over … like putting oneself to bed at night and getting out of bed in the morning.

Still life photographs are not pictures taken by a camera. The photographer makes the picture and tells the camera how to take it. The camera, not the subject, is told to be still and not even think, just look. Then the life of the still life that is about to become eternal (forever a photograph) is cut short by a blink of the camera’s eye. The cut flowers wilt, the fruit rots, the dewdrops evaporate, the butterfly’s wings crinkle, the vase is put back in the cupboard. In the chain of history, life, which is never still, comes before death. If there is any intellectual value to the notion of trompe l’oeil (trick the eye), greater value surely accrues to trompe mort (trick death). Nature morte can also mean that death is natural.

Walking the streets of New York City, I look for dead bugs to put in my pictures. Once I found a praying mantis that was intact, and the butterfly that’s in Peonies. I found a huge queen bumblebee that must have bumbled into a passing car, and on another day, I saw a grasshopper where for blocks around there was no grass to hop over. I was about to pick it up when I saw that it was plastic. On a recent trip to Nantucket, I found a horseshoe crab and other dead crabs. I put them in a box and took them back with me to Manhattan. I had to soak them in my bathtub with Clorox to get rid of the awful smell.

For the present to be present, it must have a face on the past. Behind that face, time’s past fades into memories. “I have always been attracted to the magic of objects that evoke memories, Paulette says. “Being a sentimental person, capturing moments in photography brings me back to past feelings so I can savor them again.” Every element in her still lifes has another life in memory. Like the dual life of a butterfly—does it remember having been a caterpillar? Does the frog remember when it was a tadpole with a wriggly tail and could breath under water? Does the fading rose remember its virgin youth as an innocent pink bud before it was burned on the Altar of Love by the heat of Hymen’s torch?

I wanted to find a naturally grown rose for putting in Strawberries, and found one when riding in a taxicab. Through the window, I saw a rose bush and had the taxi stop so I could jump out and pick a flower from it. That rose now rests partly on a rock and partly on a crevice. Trying to keep its balance.

Without a fixed place in nature and submitted to arbitrary and often accidental manipulations, the still life on the table is an objective example of the formed but constantly rearranged, the freely disposable in reality and therefore connoting the idea of artistic liberty. The still life picture, to a greater degree than the landscape, owes its composition to the artist, yet more than that it seems to represent everyday reality. —Meyer Shapiro, 1968

As for the Strawberries, I spent day and night of the 4th of July weekend just setting it up. As soon as I had cut the leaves from the stems, they wilted and died, so I had to cut off lots of leaves as replacements. Because it was dead and as dry as a mummy, I had to steam the large insect to soften it so with tweezers I could separate the legs and the antennae that were stuck together. When I placed the lifelike insect in the composition, the strawberry above it came crashing down and broke off one of the antennae … (that would have happened in nature, too, I suppose).

After the shooting, to celebrate, I made an old fashioned strawberry shortcake heaped with whipped cream. As in my still life, the shortcake’s strawberries struck me as very dissimilar people: different faces and personalities, some guarding their space, others leaning to reach another, some looking silly, some old and some just starting to live, some sexy and some decadent. But all were perfectly delicious.

During the tenth sitting of Ambroise Vollard for his portrait by Cézanne, Vollard dozed off, slid from his model-stand chair, and crashed onto the floor. Cézanne scolded him for getting off the pose and ordered him to get back in his chair, resume his pose, and hold still as if he were an apple. As for his still lifes, Cézanne would rarely finish one on the same day he started it, so his apples rotted, couldn’t even be eaten. And he refused to paint cut flowers, as Monet and Renoir painted, considering the short life of flowers in bloom. But in his day, every proper household had in the salon a bowl or basket with plaster fruit. Cézanne bought a basket of plaster apples and pears that would forever look the same, gathering dust but never rotting.

While planning to shoot Pears, I found that I needed one more pear. It was late at night. Grocery stores were closed. But luckily, I remembered I had purchased a ceramic pear when living in Santa Fe. Voila! It completed the composition.

Watermelon Radishes is among my favorites. It took an entire week to get the lighting just right. By the end of the week, the root on the left had reached out of the frame and then curled onto its self. The radishes and the roots touch each other—a tentacle touching an open leaf, like an embrace or as if holding hands. They dance with each other. The green ceramic bowl I made myself.

I am always careful not to dislocate leaves from the fruit, but while setting up the shot, one leaf broke away, leaving it by itself, alone. So accidents are sometimes the way things should happen.

All of Paulette’s still lifes are about the simplicities of life: seeing and feeling the birth of things, aging while seizing precious moments, facing up to the fragility of love, balancing emotions on thin high-wires, hiding secrets in sealed tombs, suffering desires—tempus fugit, loving and being loved, passionate in relation to one another, touching, embracing, huddling, and with tears of joy or sadness being cradled and comforted on nature’s lap. Oddly, her still lives are not still, but like her, are scrambled with life.

Wayne V. Andersen

About Wayne V. Andersen

Until his passing in January 2014, Wayne Andersen was Emeritus Professor, History, Theory and Criticism of Art and Architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His essays on art and literary criticism are widely published in Europe and America, and he is the author of 11 books on subjects ranging from Cézanne to Picasso. His most recent book is Marcel Duchamp and the Debasement of Modern Art.